Mr Schmidt, we are delighted to be joining you here in your home, which is just a few kilometres north-west of what is still the Aebi Schmidt Group’s biggest production facility, in St Blasien. When you celebrated your 95th birthday, the “Badische Zeitung” newspaper wrote that you used to spend every winter travelling through the highest regions of Europe, presenting and selling snow clearing machines. Do any of these trips stick out in your memory?

It’s hard to say, there were dozens of trips. But probably the Himalayas. It was on one of my trips to Japan in the early 1970s. We took a detour to a Himalayan pass, the Zoji La, which runs at an elevation of over 3,500 metres and connects Ladakh to Srinagar. It was in response to a call for tenders from the Indian Army. We actually scored really well, but we had no chance of winning it. The competition had representatives who got there faster than we did. Of course, it was tough to realise that the die had already been cast before we even joined the game. But a couple of years later, that’s when we got to make our move after all. The competitor had provided machines which were not tried and tested, and they apparently performed really badly, so our representatives had no trouble in winning the order the next time the tender went out. We are talking about 22 or 24 machines. It was a huge order.

Is the condition of the snow in the Himalayas comparable to that in the Black Forest?

It’s the same as that in the Alps. But the safety measures in the Himalayas were absolutely terrible. Every evening we were just happy to get home in one piece. They had some pretty strange ideas about safety – or none at all.

People say that you know a lot more about snow than any polar explorer.

[Laughing] Oh, that’s overstating it, of course. But the different types of snow do reveal themselves to you when you’re clearing it. Because it’s often the case that snow is not pure. Layers containing sand or dust tell you a lot about the snow’s origin or condition.

You are a German and European senior long jump champion, the proud owner of numerous gold German Sports Badges, used to shoot pistols, were a cyclist, took part in ski marathons … the list goes on. How did this passion for sport come about?

It started with the German Sports Badge. I scored well the first time, and that prompted me to take part in the contest every year: 25 times in all. You can imagine that in the summer you need to do something other than snow clearing. I was surprised that I was still able to perform well, despite my advancing years.

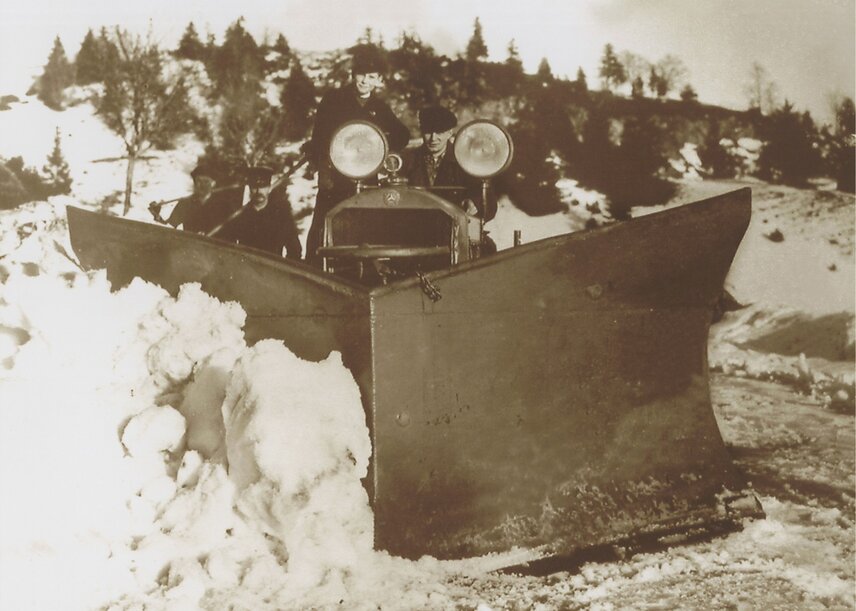

Let’s turn the clock back 100 years. How did your father start the business?

It was after the First Word War. At 18 years old, he was a driver in Crimea. After he returned, he set up a little bicycle shop together with my grandfather, who was the foreman at the spinning mill in St Blasien. That’s where I got my love of bicycles from too.

Lots of the company’s inventions and patents can be traced back to your time at the helm. Which ones are you especially proud of?

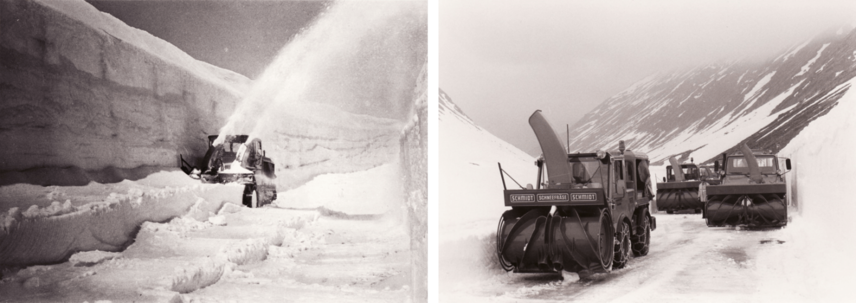

An example of a smaller invention that I was also proud of was when we developed the ability to control the ejection chute on the snow blower. Looking back, our invention of layer-cutting technology that enabled snow to be cut at heights more than twice the diameter of the cutter head was one of our greatest achievements. But unfortunately we could not patent it. We often found ourselves cutting snow layers on passes which had never been cleared before. I drove all the machines myself – for me, that too was a kind of sport.

The first volume of the book “Geschichten rund um den Unimog” [“Unimog Stories”] contains a wonderful line: “Layer cutting meant that, for the first time, I could cut snow that was even higher than the snow clearing head. The onlookers gasped: we had made the impossible possible once again.” People thought it simply couldn’t be done, and you did it anyway?

Yes. That was in 1963, I believe. Clearing the Great St Bernard Pass. We turned up at the uncleared pass, on purpose with our small machines – the Unimog with 30 horsepower, but with creeper gear and four-wheel drive – and offered to clear it. Hardly anyone believed we could manage it, but just a few days later the job was done.

For a long time, Schmidt and Unimog were closely linked in terms of how their technologies developed. How did this collaboration come about?

A businessman in the St Blasien area had bought a Unimog. He approached me about attaching a snow plough to it, because his district had awarded him the contract to clear its snow. So we developed an attachment system for it, which later became the industry standard. But even before that, the people at Mercedes-Benz had been aware of our project at the Great St Bernard Pass and had been there for that clearance. After that, there was a little competition between us. The developers at Mercedes-Benz had attached one of our snow ploughs and used compressed air to operate it, but they could not raise the plough very smoothly, nor could they hold it down at the bottom well enough. Snow doesn’t yield just like that, and you have to be able to keep the plough in the position where you need it. However, our mechanical lifting and lowering system was more successful – even though it was actually much more primitive than the compressed air system used by Mercedes-Benz. Their Unimog dug itself in, the wheels started to spin and after a few metres it was game over. Our plough, on the other hand, was kept stable by the mechanical lifting and lowering system, and cleared the slope with no problem at all.

And that’s how the collaboration with Mercedes-Benz began?

Yes, to start with it mostly took the form of joint exhibitions at trade fairs, which we and Mercedes-Benz staffed together. This meant that we came into contact with their customers too. Another rather important collaboration were the demonstrations that we would organise every couple of years at different high-altitude passes, before we settled on the Timmelsjoch Pass as the venue for our major events. We spent three weeks clearing the pass there, taking the opportunity to showcase our latest snow clearing machines up on the pass itself, along with the rest of our product range, including our summer machines and especially our sweepers, down in the valley. We often welcomed over 2,000 visitors from a good three dozen countries. It was our industry’s most international event. Not only were we able to show our latest machines, we were also able to build relationships with our customers: advertising alone will never give you that edge. We felt at home on the Alpine passes. When it came to clearing snow, nothing could phase us. For instance, take a look at this photo here in this book [he points to a photograph]: a slope with a 30° incline. You couldn’t clear snow like that with a machine. On the Grossglockner mountain they had six to eight workers whose job was to shovel a ledge into the slope. And I thought there just had to be a way of doing it mechanically instead. So I developed the “cutting auger”, which you could rotate in both directions, depending on the terrain. It enabled you to pierce directly to a depth of 1.80 metres.

You studied mechanical engineering. What would be your advice to apprentices starting their mechanical engineering training at the company today?

[Laughing] Well, you’ve always been able to go far with mechanical engineering and that’s still, actually it’s especially true today. I know from my peers and colleagues that no one ever had a problem finding a job. So they don’t need any particular advice from me.

I would like to stay on the topic of trainees and apprentices a minute. When we were preparing for this talk, we asked our apprentices what they would ask you. One of the trainees from our factory in the Netherlands had this to ask: “How did Schmidt stand out from the competition back then?” You have already mentioned about keeping the plough held down and surpassing the cutting height. What else did people say back then? Schmidt is different because …?

We were different because we tackled things head on without preconceptions and we were open to everything. That really was our method. Just like that time I mentioned on the Great St Bernard Pass. When we arrived there with two small Unimogs, everybody just shook their heads and said: “With all due respect, come back in four weeks, half the snow will have thawed and gone by then.” And we replied: “No, we think we can do it.” It was a proper adventure. The Great St Bernhard Pass isn’t the highest pass, but it has lots of turns and back then there were huge snow drifts. What we dared to do there was actually pretty bold.

There was another question in the same vein. This one comes from three apprentices at the St Blasien factory: “In your opinion, what was the crucial factor behind a ‘small’ snow plough manufacturer like Schmidt breaking through to become a global brand?”

It was our collaboration with the Unimog, which was initially only intended for agricultural use. We opened the door to local government contracts for them, and suddenly we had access to the Mercedes-Benz sales organisation, which had over 30 general agencies in Germany alone. Just like that, we had 30 retail outlets and Unimog was happy to have a new, attractive sales market to develop in the shape of municipal authorities. We established ourselves on foreign markets very early, often working there closely with Mercedes-Benz.

Today, the Aebi Schmidt Group has grown into the market leader, especially when it comes to the airport business. Can you remember the first time you approached an airport?

I don’t know now when it was exactly. But Frankfurt Airport was definitely one of our first major customers. There were lots of other airports, not all of them in Germany, that were interested in clearing their snow too – not only using ploughs, but also with rotating machines. Back then, we had proper snow! Airports were constantly battling against the walls of snow left at the sides of the runway after clearing. They already had ploughs, but they also needed to get rid of those walls of snow, otherwise their runways would become too narrow. We chose a high-performance Kaelble machine as our base vehicle. Before then, no one had thought to use these powerful machines for this purpose. But I was ambitious and able to persuade Stuttgart Airport to try it out. It’s a great feeling to invent such a beast of a machine, which has an 800-horsepower drive unit for the cutter and around 300 horsepower for the vehicle.

Thomas Berger adds: The Kaelble is still operational at Stuttgart Airport to this day. It has been overhauled twice in the intervening years, the last time almost a decade ago at our factory in St Blasien. The VF7 cutter on the base vehicle is still running and is treated like a treasured possession. It is no longer used every year, but it is always ready to go as a reserve, and may only be driven by the workshop supervisor. Thanks to its latest overhaul, it looks spick and span.

Stuttgart is still an important partner to Aebi Schmidt today. We are working together with another industrial company to develop autonomous operations for the airfield at Stuttgart. Back when you were in the thick of things, did you ever think that these vehicles might one day drive themselves?

Oh no, not at all.

Let’s leave snow behind for a second: how did the company first get involved in the sweeper business?

It was the idea that there had to be summer equipment too. We needed something that was in demand the whole year round. In business, you can’t put all your eggs in one basket. Plus the winters were not very reliable; in fact, some were disappointing.

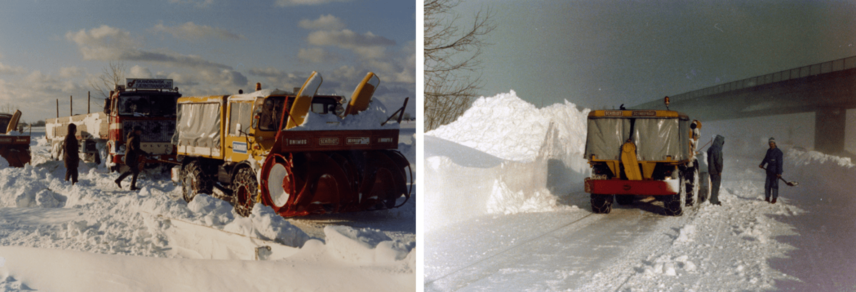

Although 1978/79 was a “once in a century” winter, with the whole of Germany under snow.

Yes, we sent two snow cutters to the north of Germany to help clear the roads there. We didn’t abandon our customers and we even managed to sell a couple of machines that way too. It was a good advert for us. We were on hand when the situation got serious. Some villages and towns were completely cut off to traffic. The impact it had was quite incredible. Even trains were stranded. Some of the snow clearing done at low altitudes wasn’t very professional – or it just wasn’t done at all. We even sold a snow cutter to the city of Lübeck. [Laughing] Not long later, they sold it back to us.

Do you believe a fully electric Supra or one powered by fuel cells will soon make its way up as far as the Krunkelbachhütte one of the highest-altitude mountain restaurants in the region?

Yes, I do believe that.

To what extent has the Black Forest influenced how Schmidt has developed over the last 100 years? Would the company have grown in the same way had it been located in the north of Germany?

I doubt that it would. The snow here was clearly the decisive factor. After all, the first snow ploughs that my father built were absolutely vital. Before that, people only had ploughs that were pulled over the snow by oxen. The first snow plough mounted on the front of a truck was a sensation.

Production was always in the centre of town, in various buildings and at different levels. What motivated you to keep the business in St Blasien?

To be honest, I never thought of moving it anywhere else. The area was very important to us in terms of our employees. We always had really good, reliable people from the surrounding villages. That was a crucial point.

How did one of your machines find its way to Antarctica?

In South Africa, there was a call for tenders for snow clearing machines that would be used in Antarctica. They were primarily interested in machines with a crawler drive. But in the end it fizzled out. After that, I was on a trip to South Africa with a trade association, so I took the opportunity to go to the Ministry of Transport in Pretoria and enquired whether they were no longer interested in our offer. The response came that they were indeed very interested, but when planning their budget, they had forgotten to include transport costs. And that’s not an inconsiderable sum all the way from Germany to South Africa. So I suggested moving the transport costs to next year and the next budget. I called our workshop manager from Pretoria and asked whether we could still do it in time. He said that, with overtime and Saturday shifts, we could manage it, so we submitted our offer. They ordered the machine there and then. I think we supplied six or seven machines with crawler drives to the Antarctic, which were then used by the German, Australian and other research stations. I was invited to travel to the Antarctic on board the “S. A. Agulhas” research vessel as a thank you. That was a truly unique experience. As was the terrible storm with force 10 winds and a 45-degree list on the return journey!

Training has always been important to you as a way of attracting people to work for the company. We now have some employees who are the third generation of their family to have also done their training with us. Why was training so important to you?

It was just so obvious to me. There were lots of families where the father already worked for us and the children were interested too. I think that was what drove us to set up a department for trainees, which was separate from Production.

Let’s end our conversation with a question posed by one of our apprentices from the Burgdorf factory in Switzerland. Feel free to close your eyes, as her question is this: “When you hear the name Schmidt, what do you see?”

Well, first of all I see snow clearing, of course, because that’s the activity that has given us so much adventure. I see us in India, for example, on the Zoji La Pass, and in dozens of other countries on all five continents. How else would I have managed to get to all those places in my life? And when you’re being financially successful and getting recognition for your technical achievements as well, it really is the best.